In my role leading the Undergraduate Research Initiative, I’ve had the privilege of working with incredible educational professionals who’ve transformed my thinking about teaching, learning, and leadership. Today, I’m excited to share insights from a conversation with Rachel Stewart, an evaluator whose work has been instrumental in helping us understand the impact of undergraduate research experiences at our institution.

The Path to Becoming an Evaluator

Kyla: Rachel, I want to know what led you to become an evaluator in higher education. Was there a particular experience or mentor that shaped your path?

Rachel: For me and I think for most evaluators, you kind of stumble on it by accident. In my case, it wasn’t one big accident, but several little accidents with colleagues in the teaching and learning space saying, “You’re really good at this. You should look into it further.” So, I did on my own time and found ways to bring what I learned into my work. And next thing I know, I had an official evaluation title.

Evolution in Evaluation Practice

Kyla: How has your approach to evaluation evolved over your career? What’s the biggest shift in your thinking?

Rachel: At first, I was really focused on outcomes and impact because that’s always what “the ask” is. But I’ve learned over time, especially with the projects and collaborators I work with, it’s more meaningful and effective to start with the learning first and then think about the program’s outcomes and the impact second. You get to what’s really of interest and what’s important to them by asking, “What do you want to learn?”. Then, you can step back and ask, “what is the alignment between what we want to learn and big picture things like institutional strategic plans, unit plans, and terms of reference, etc.?” There are always connections, and the path between “what have we learned” to “what has been the impact of our program” becomes a little bit clearer. It helps you identify the core evaluation questions, even possible data sources and data collection methods.

Kyla: Do you mean put the “learning first” in terms of what you want to learn, or what you have already learned, or both?

Rachel: Definitely both. I always start with “What do you want to learn about your program this year?” It could be about its design, its participants, or its materials. Depending on the program, I can then ask, “What have you observed about your program in the past?”

Unique Challenges in Higher Education Evaluation 🧩

Kyla: What unique challenges do you find in evaluating programs specifically in the post-secondary context?

Rachel: The complexity of a university as an organization. There are so many different agendas, interests, values, and assumptions going on – not just within how different offices work together, but in terms of answering the question, “What is the purpose of higher ed?”

That complexity also applies to people. In higher ed, you have people for whom this is their job, their nine-to-five. But you also have people for whom this is their vocation – their identity is tied into their work. This is when evaluating a program starts to touch on concerns like, “Are we also evaluating your teaching?”. I see my role as discerning and recommending how to maximize what we can learn from the evaluation while minimizing harm to the anyone involved.

I love that complexity, though. Every time I talk to a more senior evaluator, they say, “We don’t get into this work because it’s vanilla. We do it because it’s juicy, because it’s spicy.”

Core Values in Evaluation

Kyla: I’m curious about your evaluation philosophy. What core values guide your work when you’re designing an evaluation strategy?

Rachel: My core values are learning, integrity, and collaboration.

Learning comes first, and it guides what questions we want to ask. I think for any evaluation, even if you’re using a very developmental approach where you’re meant to iterate what questions you ask over time, you always have to start with a question. You have to start somewhere.

Integrity is key. Even though evaluation typically doesn’t involve a formal ethics certificate, all the guidelines and practices for ethical research still apply – minimizing harm to participants, protecting data, and upholding the rights and dignity of anyone involved. In working directly with program leads, I’m thinking about potential harm to participants but also about potential harm to the staff. To illustrate, Dr. Christine Martineau and I are co-leading the TI Program Evaluation Strategy Working Group and we were thinking about the TI’s program facilitators. If someone wants to be harmful in their feedback like by giving a racist or sexist comment, they’re going to do that no matter what, but how can we make sure our evaluation designs aren’t set up to make that easy?

Lastly, no evaluation happens alone. There’s a spectrum of how an evaluator engages with interest-holders. On one end of the spectrum, an evaluator acts as an external party that looks at the program from the outside in, almost like they’re conducting an experiment. This kind of evaluation typically has things like audits built into the design. On the other end of the spectrum, an evaluator is fully embedded in the program and acts primarily as a facilitator. This kind of evaluation really lends itself to social justice work. I work somewhere in the middle and tailor my approach depending on the project. No matter what, it’s always good to have as many groups possible represented in the evaluation process. It creates shared ownership of the evaluation’s findings and helps ensure the outcome of the evaluation is actually useful. Not everyone needs to be on the evaluation team or to see every finding, but I like to share something back to anyone involved in a program. It can be something as simple as, “Thank you for offering a workshop! Care to see what participants had to say about it?” I’ve yet to have someone say they’re not interested.

Kyla: I imagine it as a snowball that keeps growing—the more people involved, the more momentum you’re building around the work because people are invested and interested, they want to hear more and learn more. It builds and grows.

Common Misconceptions

Kyla: What’s one common misconception about program evaluation that you regularly encounter in higher ed?

Rachel: Mostly people just not knowing that it is a specialized discipline. I think in general, people in higher ed know that evaluating our programs is best practice and it’s often a requirement of leadership or sponsors, but they don’t know that this can entail so much more than a survey. Often, it’s done as an afterthought or off the side of someone’s desk without much awareness of the expertise out there.

An effective evaluator draws on three things to do their work well: their knowledge of different research methods and theories, their knowledge of the context their working in, and their knowledge of evaluation-specific approaches and frameworks. That combination means they can design and implement an evaluation study rigorously, ethically, and reliably. It also looks different depending on the context it’s done in. An example higher ed folks might relate to is the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL). Like SoTL, no one field owns evaluation yet there are specific ideas that distinguish it from other areas of inquiry, and recognized scholars and practitioners who commit their careers to advancing knowledge and practices in that space.

Building Trust

Kyla: How do you build trust when working with a program that is evaluation-hesitant or has had negative experiences with assessments?

Rachel: Honestly, start where people are at. Have that open conversation: “When you think about evaluation, what comes to mind?” Acknowledge that there are a lot of bad experiences associated with evaluation, and a lot of crappy evaluations out there. It’s about actively listening to their views and discerning what steps to recommend next. In my experience, next steps have included creating a logic model or forwarding resources. Because my evaluation practice is so learning focused, I don’t want to force an evaluation on a team before they’re ready.

The Logic Model Approach

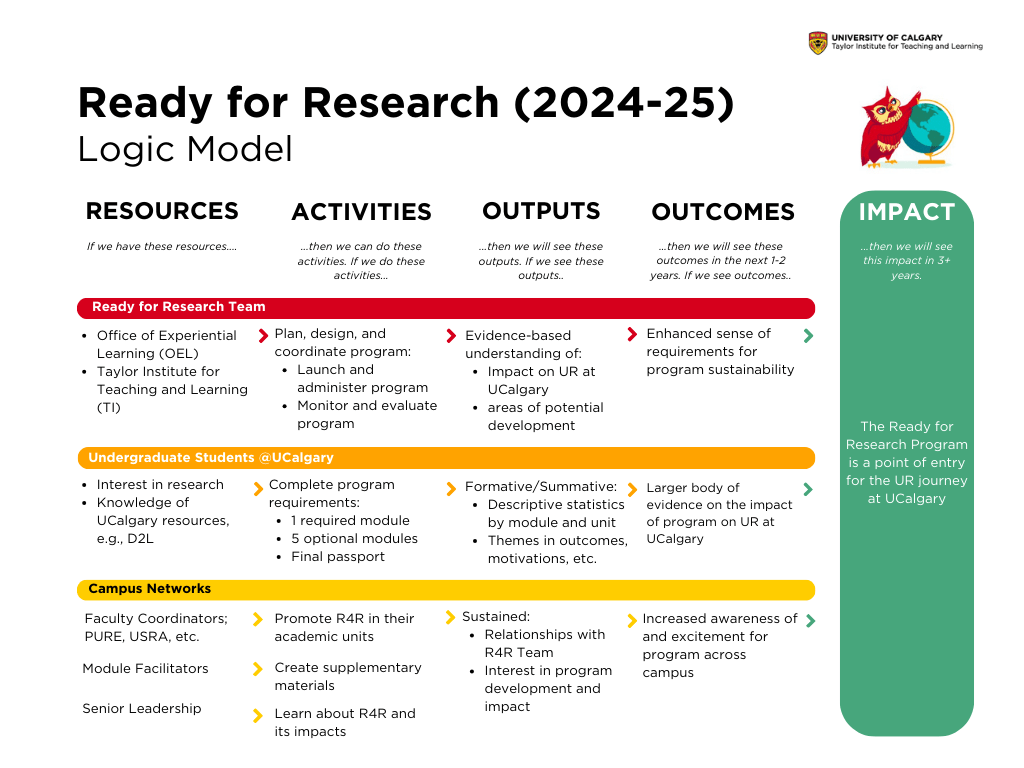

Kyla: By the point where we got to a logic model in the Undergraduate Research Initiative, it was starting to transform the work we did. Can you tell me a bit about what a logic model is and its different components?

Rachel: I love logic models – they’re one of my favorite things! A lot of people don’t like them because they’re quite linear, which is valid. It reads like “If you do A, you’re going to accomplish B” – and we know real life isn’t like that. But I like to reframe it as a reflection exercise to create a snapshot of how we understand the program at this moment in time.

Every logic model has the same basic ingredients. Essentially, imagine a table made of five different columns: resources, activities, outputs, outcome, and impact. You have your planned work as the first three columns and your intended results as the last two. You read it as a chain of if-then statements.

- First are resources – “If we have the following resources…” then

- Activities – “…then we can do the following activities.” These are what your program does in its regular operations – offering workshops, planning, reporting, whatever your group defines as its regular work.

- Next are outputs – “If you do these activities, then you’ll see the following outputs.” These are things like number of participants, documents, processes, reports, lists – anything that shows your activities happened at the right dose.

- Your outcomes or intended results are next. “If you have those outputs, then you’ll see the following outcomes.” These are the change statements, like “Participants leave with an increased sense of identity as a researcher” or “We have enhanced relationships with our campus networks.”

- The last is impact – “If we see these outcomes, we’re going to see this impact.” This is where the exciting stuff lives, like your mission and vision or “the why” of what makes you do the work you do, like “Undergraduate research becomes a hallmark of the undergraduate experience at UCalgary”.

Kyla: There’s something about the name “logic model” – it sounds so much less complicated than it actually is! But what I appreciated about doing a logic model was the time and space to dream big about why we’re here. We don’t often take time to do that in our busy workdays. The logic model framework resonated with me as a teacher because it was aligned with backwards design – what do we want to do, what do we want to be, and how are we going to get there?

Rachel: It’s can be very practical for the evaluation design, too. For instance, what goes in your Outputs column becomes the basis for your indicators, even your methods. When I hear colleagues say, “we want to learn about our participants”, I immediately know that for indicators, we need counts and characteristics, and for methods we need a process to collect and monitor it all. Here’s an example of what this looks like for the Ready for Research program:

Creative Data Collection

Kyla: If you think about all the different ways you’ve collected data as an evaluator, was there a method that was particularly rich or creative that surprised you?

Rachel: I was incredibly surprised to see a format I call “mini stories” be as effective as it is. These are short first-person narratives from program participants on the impact of their program experience on them. A few years ago, outside of work, I was volunteering with a magazine writing their monthly features. I had to learn how to get to a story quickly without reusing the same narrative structure. I thought about how to shrink that down to something I could use at work. What started as collecting two or three stories for a report has grown to a library of over 70 first-person narratives of participants in the same program over the last four years. It’s illuminated elements of our program we never would have known before, like how different undergraduate research looks across faculties. We’re starting to understand that there isn’t one undergraduate research journey at UCalgary – there are several possible journeys, each with different terrain, seasons, and guides. See here for examples of these stories for the Program for Undergraduate Research Experience.

The Future of Evaluation in Higher Ed

Kyla: What do you see in terms of the field of evaluation in higher education? Where is it heading? What emerging practices are exciting you?

Rachel: I’m still learning what this looks like. I don’t know of another person with a specialized role like mine on campus, though I do know many people are doing something elevation-adjacent for their programs. From what I can see, things are very output-focused – we need reports, data visualizations, slides, quotes, and we needed them yesterday, but how people are doing this isn’t being shared. I’m attending the Canadian Evaluation Society annual conference in a few weeks, and no one is presenting on higher education. Presenting on government, health, or non-profit work, yes, but not higher ed. I think there’s a lot of room for growth, and the conditions are ripe for it.

Advice for Getting Started

Kyla: If someone reading this is inspired by your journey into program evaluation, what advice would you give them to get started?

Rachel: Honestly, start by thinking about what you want to learn about your programs. There are good resources out there:

Eval Academy – My favorite online resource to get excited and geek out, run by Three Hive Consultancy out of Edmonton

Better Evaluation – a very long-running evaluation resource website

The Canadian Evaluation Society – has job postings and resources (some paid, some free). They are also the credentialing body for the Credentialed Evaluator designation

Higher education online certificates – I did mine through the University of Victoria (Graduate Certificate in Evaluation)

The Best and Worst of Evaluation Work

Kyla: To wrap things up, what are the best and worst parts of being an evaluator?

Rachel: For me personally, the worst thing is seeing a missed opportunity to for evaluative thinking to be useful. It pains me when the interest and curiosity are there, but due to a lack of expertise or resources, a survey or focus group is designed that’s ineffective. Worst case scenario, it hurts our reputation and credibility because “the ask” of participants is unclear or mis-timed. More commonly though, something is collected, but not something necessarily useful or even interesting, which impacts the learning from the whole exercise.

The absolute best thing is when people come excited to try evaluation for the first time or dig deeper into what they’re already doing. There’s also that moment at the end of an evaluation when you’ve collected and synthesized all the feedback and talk about it with colleagues. Seeing that learning happen is everything.

Kyla: Those hidden insights are things that we would never have known without the work you’ve done.

Thank you for sharing your expertise with me! ❤

Check out the Taylor Institute Reports and Plans website to see Rachel’s amazing evaluation reports!

Leave a comment