Many educators view experiential learning as hands-on “learning by doing.” However, through our work at the University of Calgary’s Office of Experiential Learning, my colleagues and I have come to realize that this definition doesn’t quite capture its full essence.

Revising a Framework: A Simple Update Prompts Deep Reflection

In 2023, a team at the Office of Experiential Learning was tasked with updating the University of Calgary’s Experiential Learning (EL) Framework. The existing framework, written in 2020, organized experiential learning into five categories: curricular EL, co-curricular EL, community-based EL, research-based EL, and work-integrated learning.

My colleague Dr. Lisa Stowe shares her perspective on the process:

“I was proud of UCalgary’s 2020 Experiential Learning framework and definition. Having been involved in the original working group that meticulously crafted the definition, I understood our struggle to encompass all EL activities across campus. The definition, though lengthy and difficult to memorize, effectively captured the ‘hands-on’ learning taking place university-wide, with thoughtful and thorough examples.

So, in Fall 2023, when the Vice-Provost asked me and Kyla to revise these guiding descriptions, I thought, ‘How hard could it be?’ Just update some language based on the past three years of EL conversation with the UCalgary community, including some more examples that better align certain definitions with national EL discussions. Simple wordsmithing, right? I was so wrong, and not at all prepared for where this revising would take me.

Like all good experiential learning practice, I should have checked my assumptions and biases at the door. Because revising and updating the EL framework and definition turned into a deep conversation with Dr. Christine Martineau about the colonialism inherent in our current documents and a process that would lead to an alignment between our EL Plan and Indigenous Ways of Knowing, making the definition and framework more holistic and multidimensional and accessible to so many EL practitioners working across campus. This ‘simple wordsmithing’ process was one of the deepest thinking periods of my academic career, resulting in a document I consider among my proudest academic achievements.”

What began as a minor update evolved into a profound rethinking of how we understand experiential learning itself.

Uncovering Limitations in Our Understanding

Through consultations with colleagues across campus, two significant challenges with the previous EL framework emerged:

- Many experiential learning activities defy simple categorization, fitting into multiple categories simultaneously. Conversations about which category an EL activity ‘counted’ as were generally unproductive and took away from more meaningful discussions about teaching and learning.

- Both Indigenous and non-Indigenous colleagues highlighted the Western bias in our framework, urging us to consider how EL might better align with UCalgary’s Indigenous strategy.

The process pushed us to question our fundamental assumptions about learning and recognize the limitations of “learning by doing” as a complete definition.

A More Holistic Vision: Learning by Doing, Being, Connecting, and Reflecting

Our revised definition expands experiential learning beyond activity alone:

Experiential learning is learning by doing, being, connecting, and reflecting. (Flanagan et al. 2024)

Each dimension brings something essential to the learning experience:

Learning by Being

This dimension acknowledges that learning happens when we are fully present and immersed in experiences. It recognizes students as whole people with intellectual, emotional, social, physical, and spiritual aspects. When students engage in “learning by being,” they often experience shifts in how they see themselves both professionally and personally. As Christine said we aren’t “human doings;” we are “human beings.”

Learning by Connecting

We don’t learn in isolation. This dimension encompasses the learning that occurs through relationships, with other people, with the land, with ideas, and with one’s sense of purpose. A relational approach to learning recognizes the value of communities, mentorship, and our connection to the world around us.

Learning by Reflecting and Learning by Doing

While “doing” remains important, meaningful reflection helps students integrate their experiences into a deeper understanding. Through guided critical reflection, students develop the metacognitive skills to question assumptions, analyze experiences, and articulate their learning.

A New Quality Framework

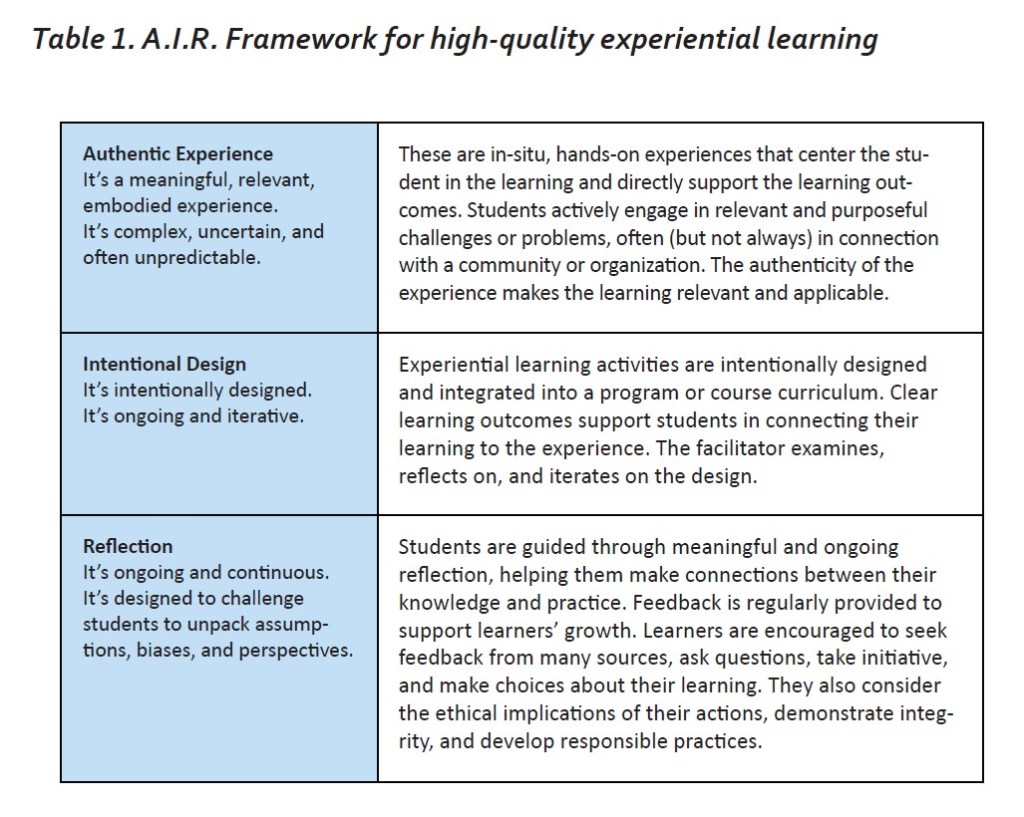

Just as our definition evolved, so did our framework for high-quality experiential learning. We adapted the PEAR framework (McRae, 2018) into the AIR framework (Table 1 from Flanagan et al. 2024):

This shift replaces the requirement for formal assessment with an emphasis on reflection and feedback, allowing diverse types of experiences to be recognized as high-quality EL.

Moving Away From EL Categories

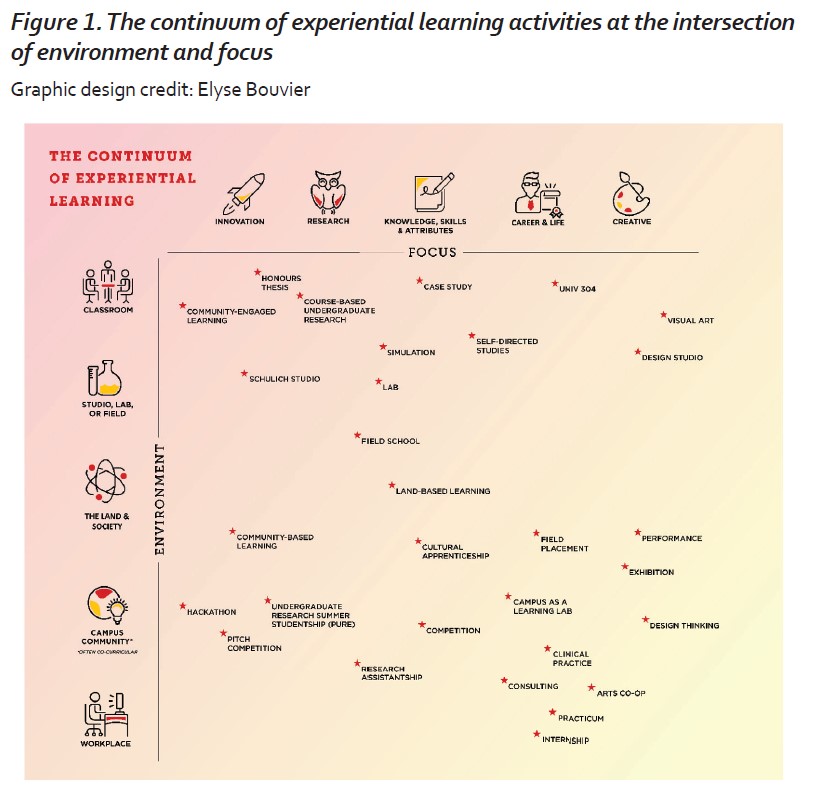

Rather than categorizing experiences, we moved towards describing experiential learning along continuums defined by:

- Environment: Where learning takes place (Classroom, Studio/Lab/Field, The Land and Society, Campus Community, or Workplaces)

- Focus: The primary purpose of the experience (Innovation, Research, Knowledge/Skills/Attributes, Career and Life, or Creative)

This approach better captures the multifaceted nature of experiential learning while honouring diverse ways of knowing (Figure 1 from Flanagan et al. 2024). We like using this as a pedogogical tool to visual show where EL is happening and what the focus of the activites are. It provides a visual way to identify gaps and strengths in EL activities for given units.

Learning in a Good Way

This revisioning represents our commitment to reconciliation and creating more inclusive learning environments. By expanding beyond the traditional Western emphasis on “doing,” we create space for Indigenous ways of knowing that view learning as sacred, holistic, purposeful, and relational.

The EL team continues to listen carefully to feedback from Indigenous faculty members, Elders, students, and communities, with the goal of ensuring that experiential learning opportunities are accessible to all students and honour diverse ways of knowing and learning.

Questions for Reflection

- What are some ways to incorporate elements of “being” and “connecting” into existing experiential learning activities?

- How does your current approach to reflection encourage students to explore multiple dimensions of their experiences?

- How can you create experiential learning opportunities that honour diverse knowledge systems?

I’d love to hear your thoughts and experiences with experiential learning and what resonates with you in this expanded definition.

This blog post is based on “The Land and the A.I.R. – Revisioning Experiential Learning on a Canadian Campus” by Kyla Flanagan, Lisa R. Stowe, Christine Martineau, Natasha Kenny, and Erin Kaipainen, published in Experiential Learning & Teaching in Higher Education.

References:

Flanagan, K., Stowe, L., Martineau, C. ., Kenny, N., & Kaipainen, E. (2024). The Land and the A.I.R.: Revisioning Experiential Learning on a Canadian Campus. Experiential Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, 7(3 – September). Retrieved from https://journals.calstate.edu/elthe/article/view/4149

McRae, N. (2018). The P.E.A.R. Framework for experiential learning: Institutional level [PowerPoint slides, PDF file]. Retrieved from https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/sites/ca.centre-for-teaching-

Leave a comment